Image: Satellite image of sampling site and microscope images of the diatom, Climaconeis heteropolaris. Source: Cheran et al. https://doi.org/10.1080/0269249X.2025.2534369

Diatoms, the microscopic, single-celled algae, are a significant and essential component of the global ecosystem, contributing a substantial share of the world's primary oxygen production. Often found in oceans, waterways, and the soil, these tiny powerhouses are estimated to produce between 20% and 50% of the oxygen globally, making them vital to Earth's atmosphere. Diatoms are highly sensitive to environmental conditions and serve as excellent bioindicators of water quality and ecosystem health. They also form the very foundation of aquatic food webs, sustaining everything from tiny zooplankton to massive whales. Despite their immense importance, much remains unknown about the incredible diversity of diatoms, particularly in the often overlooked coastal estuaries of India.

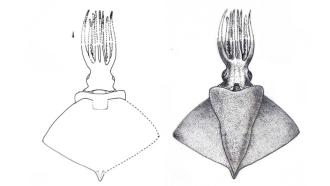

Now, a team of researchers from Agharkar Research Institute, Pune, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, and the University of Colorado, USA has added another member to this illustrious list, announcing the discovery of a new species, Climaconeis heteropolaris, from the southwestern coast of India. The discovery expands our understanding of marine biodiversity and highlights the rich, yet largely unexplored, microscopic world thriving in our oceans, even in areas heavily influenced by human activities.

Did You Know? Diatoms are often called the "jewels of the sea. Their intricate, microscopic silica shells, or frustules, have glass-like and ornate structures. When diatoms die, their glassy shells sink and accumulate over millions of years, forming deposits known as diatomaceous earth. |

The research team began by collecting stone samples from the estuarine environment where the Sita and Swarna rivers meet the Arabian Sea, near the Udupi coast in Karnataka. This specific location was sampled on December 19, 2023. The region was influenced by both human activities and natural depositional features, such as sandbars, which are partly exposed ridges of sand built by waves. Back in the lab, the collected algal filaments were prepared for microscopic examination. The samples underwent a cleaning process, oxidised with concentrated nitric acid and boiled for several hours, then repeatedly centrifuged to ensure all residual acids were removed.

Once cleaned, the diatoms were mounted on slides and examined under a microscope equipped with Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) optics, also known as Nomarski optics, which allowed the researchers to observe the diatoms' minuscule structures and capture high-resolution images. They took precise morphometric measurements, recording the length, breadth, and striae (lines) count for each specimen. For an even closer look at the diatom's ultrastructure, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was also employed, revealing the minute details of the frustule, the hard, porous structured cell wall of a diatom.

The team also employed software like GIMP for image processing. At the same time, Inkscape helped compile the plates, and QGIS was utilised for creating maps of the study sites, with Google Earth providing detailed landscape illustrations. The researchers also measured the physicochemical properties of the water at the sampling site, finding a pH of 8.06, an electrical conductivity of 55.2 mS/cm, total dissolved solids of 27.57 mg/L, a temperature of 31.1°C, and a dissolved oxygen level of 5.35 mg/L, which provides crucial context for the diatom's habitat.

The newly identified species, Climaconeis heteropolaris, stands out primarily due to its distinctive heteropolar valve shape, meaning its two ends are not identical. Its overall structure is described as lanceolate-clavate, resembling a spear or club, with rounded, capitate (head-like) apices or ends. The valve is subtly wider in its middle section, gradually tapering towards its unique ends. These microscopic organisms are pretty small, with individual cells measuring between 76.5 and 120.5 micrometres in length and 9.5 to 14.5 micrometres in width. Looking even closer, the researchers detailed the patterns on the frustule. The striae, or lines, on the valve radiate outwards near the centre, become parallel in the middle section, and then converge towards the tips, with about 17 to 22 striae packed into every 10 micrometres.

This discovery is the first documented record of a Climaconeis species from the western coastal region of India, as most prior studies on this genus in India originated from the eastern coast. The detailed morphological description, utilising both light and scanning electron microscopy, allows for a precise taxonomic placement of C. heteropolaris. The researchers meticulously compared their new finding with other known Climaconeis species, highlighting key differences. The study also recognised intriguing morphological similarities to other diatom genera like Stauroneis and Frustulia, hinting at shared evolutionary pathways. However, a more comprehensive morphological analysis could lay the foundation for future genetic and ecological investigations.

The discovery of Climaconeis heteropolaris represents another significant step towards building a comprehensive catalogue of Earth's biodiversity. Knowing the specific characteristics and distribution of species like C. heteropolaris allows scientists to better monitor the impacts of pollution, climate change, and human activities on vital coastal and estuarine environments. This research contributes to the baseline data necessary for conservation efforts, helping to protect these critical habitats that support diverse marine life and provide essential ecosystem services, including oxygen production and carbon sequestration. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of these microscopic organisms helps us safeguard the health of our planet and its oceans for future generations.

This article was written with the help of generative AI and edited by an editor at Research Matters.