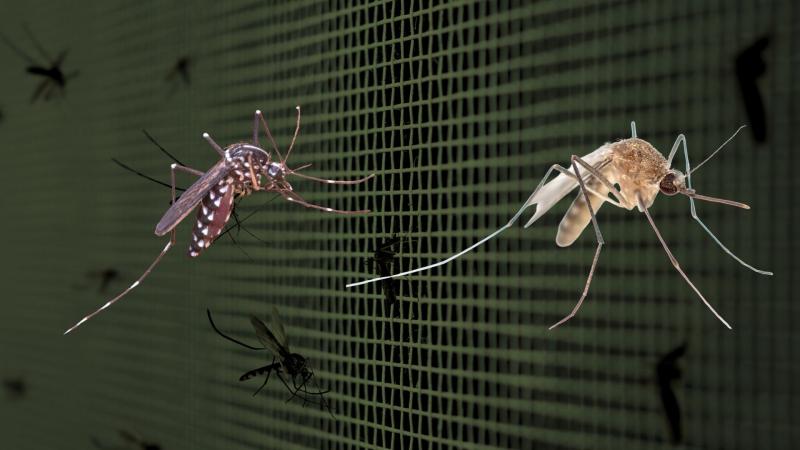

Mosquitoes are the deadliest animals on Earth, causing more human deaths than sharks, snakes, and even other humans combined. These tiny, buzzing insects, often dismissed as mere nuisances, are the primary carriers of devastating diseases like malaria, dengue, chikungunya, and Zika, which collectively claim over 700,000 lives globally every year. In India, where the tropical climate, mixed with poor water and waste management, creates the perfect environment for mosquitoes, understanding these miniature menaces is a matter of national importance.

Recently, a team of researchers from ICMR-National Institute of Malaria Research, ICMR-Vector Control Research Centre, National Centre for Vector Borne Disease Control, and others embarked on an ambitious journey across Kerala to map out the diversity and extent of these disease-spreading insects, hoping to arm us with better ways to fight back.

Did You Know? Only female mosquitoes bite. They need the protein in blood to produce their eggs. Male mosquitoes are vegetarians, feeding on nectar and plant juices. Fossil evidence suggests mosquitoes have been buzzing around for at least 100 million years, since the Cretaceous period! |

The researchers uncovered a surprisingly rich and complex mosquito community. Their extensive survey across five diverse districts of Kerala – Wayanad, Ernakulam, Pathanamthitta, Idukki, and Thiruvananthapuram – identified 108 different species, belonging to 28 distinct groups (genera). Among these, 14 species were already known to be significant carriers of diseases.

The most common mosquito they found was Stegomyia albopicta, making up more than half (54.82%) of all collected specimens. This species is a notorious vector for dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses. Following St. albopicta was Culex quinquefasciatus, which accounts for about 7% of the total and is known for transmitting lymphatic filariasis, a debilitating parasitic disease. Other essential disease vectors identified included St. aegypti, another primary carrier of dengue and Zika, as well as Culex tritaeniorhynchus (Japanese encephalitis), and Anopheles stephensi and Anopheles culicifacies (malaria). Interestingly, some malaria vectors, like Mansonia uniformis, were found in very low numbers in the study areas.

One of the most striking findings was how adaptable these mosquitoes are, especially St. albopicta. The study revealed that artificial habitats or places created or influenced by humans, like discarded plastic containers, old tires, and even latex collection cups used in rubber plantations, were hotspots for mosquito breeding, hosting a greater diversity of species (77.7%) compared to natural water bodies. St. albopicta, in particular, showed an incredible ability to thrive in 77 different types of habitats, from discarded tires to tree holes. This adaptability is a big deal because previous studies often classified St. albopicta as primarily a rural mosquito. This new research shows it's now perfectly at home in urban environments too, using our trash as nurseries.

In contrast, St. aegypti, another key dengue vector, preferred more specific spots like water storage containers in urban areas. The researchers also found that mosquito diversity varied significantly across the districts. Wayanad, with its lush forests and less human interference, emerged as a biodiversity hotspot, boasting 14 unique mosquito species. Idukki, on the other hand, had the lowest diversity, possibly due to its extensive tea plantations, which don't offer many suitable breeding spots.

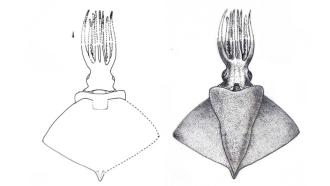

To gather their samples, the team conducted an extensive survey over a year and a half, collecting both immature mosquitoes (larvae and pupae) from water sources and adult mosquitoes using methods like sweep nets and oral aspirators. Once collected, these specimens were brought back to the lab, where they were identified under microscopes. They also looked at the species-area relationships, which are methods that help scientists understand how many species are truly present in an area and how sampling effort affects that count.

The research provides a comprehensive, multi-district snapshot of mosquito diversity in Kerala, a region particularly vulnerable to mosquito-borne diseases. However, the researchers did face some limitations. The challenging terrain and extensive geographical area of the Idukki district made sampling difficult, potentially limiting the full scope of species found there. They also couldn't conduct seasonal collections throughout the year or perform Xeno-monitoring (a technique to study what mosquitoes have fed on), which could have provided even more insights into disease transmission. Additionally, not using trapping methods in forest areas might have meant missing some Anopheles species, which are important malaria vectors..

Ultimately, this detailed mosquito census provides invaluable information. By understanding exactly which mosquito species are present, where they live, and what their preferred breeding spots are, public health officials can develop more targeted and effective strategies to control disease vectors. In a world increasingly threatened by emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, this kind of ecological detective work is essential for protecting communities and saving lives.

This article was written with the help of generative AI and edited by an editor at Research Matters.