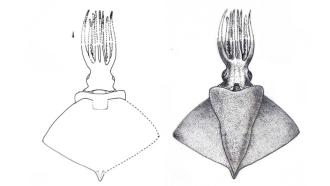

The approximately 260 kilometres of the Karnataka coastline are an essential habitat for several sea turtle species. While the Olive Ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) is the only species known to nest in the region, green, hawksbill, and leatherback turtles have also been reported along this coast. Over the years, human-driven and environmental dangers have been rapidly pushing these species toward the brink along Karnataka’s coastline.

In a new study, researchers from the ICAR-Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI) Mangalore Regional Centre and CMFRI, Kochi, have published a comprehensive assessment integrating local knowledge with other data to map the crisis facing sea turtle nesting and foraging grounds. Their study found that coastal erosion and the proliferation of seawalls, exacerbated by climate change and human activity, are rapidly eliminating critical nesting habitats for sea turtles along the Karnataka coast.

Did You Know? The sex of a sea turtle hatchling is determined by the temperature of the sand in the nest. Warmer temperatures tend to produce females, while cooler temperatures produce males. Rising global temperatures could skew the sex ratio, threatening future populations. |

The researchers employed a unique, multi-dimensional framework that integrated local ecological knowledge with other parameters. The process began on the ground, where they used a structured questionnaire and group interviews to gather insights from the resident fisher population across 33 beaches, providing a local perspective on the decline in nesting.

To assess the physical habitat, they used simple levelling techniques, a surveyor's tape, and a ranging pole to measure the slope and width of beach segments. To understand the marine environment, they collected monthly seawater samples over a decade (2010–2020) from three different depth zones (0–6 m, 10–12 m, and 18–29 m). They measured Sea Surface Temperature (SST) and salinity, and extracted Chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) to determine coastal water productivity. Finally, they used secondary sources, including data from the Indian Meteorological Department and Marine Traffic, to compile a record of cyclonic storms and analyse the distribution and speed of fishing and cargo vessels along the coast. This integrated approach allowed them to connect the dots between local human activity, global climate trends, and the health of the marine ecosystem.

The researchers found that the coastline is under severe stress. The most immediate threat comes from coastal development and erosion. A survey of local resident fishermen revealed that a staggering 52.77% attributed the loss of nesting grounds directly to the construction of seawalls and ongoing sea erosion. The seawalls, built to protect human infrastructure, now line 36% of the surveyed beach segments. Unfortunately, they also act as barriers that conflict with the coast's dynamic nature and block turtles from reaching suitable nesting sites.

The impact is visible at Panambur Beach. The shore beneath a watchtower has been completely eroded, with the high tide line now reaching above the structure, representing a significant loss of beach area over a little more than a decade. Overall, the maximum nesting area available was found to be a tiny 0.068 square kilometres per kilometre of shore.

While the olive ridley turtle was the predominant species recorded in sightings and strandings, the study also confirmed the presence of green and hawksbill turtles. Beyond physical barriers, the researchers identified other human factors, like artificial lighting, which 25% of residents cited as a significant deterrent to nesting, and increased vessel movement and beach litter were also contributing factors.

The threat from the open ocean is also significant, with vessel traffic analysis showing that the region experiences as many as 500,000 vessel movements per 4.8 square kilometres annually. The analysis of vessel traffic, which showed that 56% of fishing vessels operate at speeds below 0.6 knots, also revealed a key conservation engagement opportunity.

The study also looked at the impacts of climate change and ecosystem health. Between 2012 and 2023, the Indian subcontinent experienced eighty-eight North Indian Ocean storms, highlighting the urgent need for climate-resilient conservation. These extreme weather events accelerate erosion and inundate nests. To understand the health of the foraging grounds, the researchers analysed coastal water productivity over a decade. They found that 45.9% of the observations were classified as having 'good' trophic status, a measure of phytoplankton, the base of the marine food web. However, sea surface temperature (SST) and Chl-a levels differed significantly between nearshore and deeper waters, suggesting that coastal currents and significant climate phenomena, such as El Niño and La Niña events, influence ecosystem dynamics.

By combining local ecological knowledge with spatial, climate, and vessel traffic data, the researchers created a holistic, integrated assessment of threats. The study emphasises that static structures like seawalls are not a long-term solution. Instead, the work advocates for a shift toward “living shorelines," which use natural materials and native vegetation to stabilise coastlines, reduce wave energy, and promote ecosystem health. This approach, combined with strategic beach slope modifications, offers a sustainable solution that benefits both turtles and coastal communities.

This article was written with the help of generative AI and edited by an editor at Research Matters.