India is on a mission to eliminate Lymphatic filariasis, commonly known as elephantiasis, a mosquito-borne disease, by 2027. The disease is caused by parasitic worms known as filarial worms and are usually acquired in childhood. It is a leading cause of permanent disability worldwide, impacting over a hundred million people. India’s ambitious goal requires health officials to be absolutely certain that the disease is eradicated, not just from areas where it was common, but also from places where it was never considered a problem. To do this, researchers need reliable methods to check if the parasites that cause LF are still present, even in areas where there have been few cases.

Research from the ICMR-Vector Control Research Centre, Puducherry, and the Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Chennai, set out to compare different methods for detecting lymphatic filariasis in Salem district, a region that wasn't considered a major hotspot for the disease. Their mission was to determine which strategies are most effective in confirming whether LF transmission has truly stopped. They looked at four main approaches: school-based Mini-TAS (Mini-sTAS), community-based Mini-TAS (Mini-cTAS), molecular xenomonitoring (MX), and purposive sampling of high-risk areas. They then compared these with a large-scale community survey that acted as their benchmark.

Did You Know? Lymphatic filariasis is also known as elephantiasis because it can cause severe swelling and disfigurement of body parts, usually the legs and arms. The parasite that causes LF is spread by mosquitoes, and it can take many years for symptoms to appear, making it a silent disease in its early stages. |

Tiny worms cause lymphatic filariasis, and the primary method for detecting the disease is by examining signs of the parasite in a person's blood or body fluids. The TAS part, which stands for Transmission Assessment Survey, is a key tool recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Mini-TAS specifically focuses on children aged 9-14. They tested these children for circulating filarial antigen (CFA), a marker left behind by the parasite. If a certain number of children in a school or community test positive for CFA, it suggests that the parasite might still be around. The researchers used two versions: Mini-sTAS, which involved visiting schools, and Mini-cTAS, which involved sampling from communities.

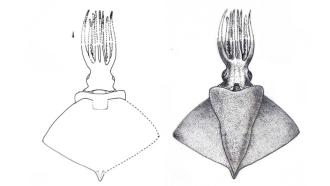

The other method they explored was molecular xenomonitoring, or MX. Instead of testing people directly, they looked for the parasite's DNA in mosquitoes. Specifically, they collected female mosquitoes that were ready to lay eggs (gravid females) to find any traces of the parasite's genetic material. This method is considered more sensitive than checking for CFA, especially in areas with very low infection rates.

The fourth strategy was purposive sampling. This involved identifying specific areas within the district that had a history of LF cases, even if the number was small. The idea here was to focus on places that might still harbour the parasite. They tested people in these high-risk sites and also collected mosquitoes for MX testing.

The researchers compared the results from these four methods with those from a large-scale survey involving over 10,000 people from randomly selected areas. This comprehensive survey provided a general picture of the situation across the entire district. The large-scale survey showed a very low prevalence of CFA, much lower than the WHO's threshold for an area to be considered endemic. Similarly, the Mini-sTAS and Mini-cTAS methods also indicated that LF was not actively spreading among children in the district. The MX surveys also found a very low rate of parasite DNA in mosquitoes. All these results pointed towards Salem district being non-endemic for LF.

However, the purposive sampling strategy, which focused on those few areas with a history of cases, painted a slightly different picture. In some of these high-risk sites, they found a higher number of people with CFA, and in some cases, the mosquito samples also showed traces of the parasite. This suggested that even in a district considered non-endemic, there might be small pockets where transmission is still occurring, especially in areas bordering districts that are known to have LF. This highlights the importance of looking closely at these border areas.

The study also explored the factors that might be associated with having CFA. They found that living in a part of the district that borders an endemic area increased the chances of having CFA in the randomly selected areas. In high-risk areas, being older than 40 and living in a community where mosquitoes were found to be infected were associated with a higher risk of having CFA. This indicates that where you live and your age can influence your risk.

Comparing these methods, the researchers concluded that the Mini-TAS (both school- and community-based) and MX surveys are effective tools for gaining a broad understanding of whether a district is endemic or not. They are consistent with the large-scale survey and can help confirm the absence of widespread transmission. However, for pinpointing those hidden pockets of infection, especially in areas bordering known endemic regions, the purposive sampling approach, combined with MX, is more effective. It's like using a wide-angle lens to see the whole picture, and then a magnifying glass to examine the details in specific spots.

The findings of this study are of great importance for India's goal of eliminating lymphatic filariasis. By identifying the most effective and reliable methods for detecting LF, especially in areas that are not currently under mass drug administration (MDA), health authorities can ensure that no cases are missed. This targeted approach enables a more efficient use of resources and facilitates the final push towards certification by the WHO, allowing India to declare victory over this debilitating disease confidently.

This article was written with the help of generative AI and edited by an editor at Research Matters.