Image: Brown female and yellow male Asian Common Toad (Duttaphrynus melanostictus) in amplexus in their natural habitat in Karnataka. Credit: American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists; https://doi.org/10.1643/h2024105

The Asian Common Toad or Duttaphrynus melanostictus is a rather dull-looking brown toad, and, true to its name, is common across India and other Asian countries. Its successful spread has even made it a dangerous invasive species in Madagascar, where it decimates local wildlife. They are usually found leaping around in agricultural fields and other urban areas with human habitation. However, with the monsoon's first rains, this otherwise dull creature undergoes a captivating transformation. The males of the species don a bright yellow suit and congregate in their hundreds for a phenomenon known as an explosive breeding event, where hundreds of individuals gather in one spot for a very short period to find a mate.

Although the behaviour has been observed and detailed, both in scholarly work and in indigenous and traditional knowledge, the reason for this transformation had not been understood. Bright colouring in nature often comes with a risk of attracting predators, but it also makes finding a mate easier. It was widely believed that the colour change in the Asian Common Toad was to benefit mate selection, but this had never been studied or confirmed.

To settle this question, researchers from the University of Vienna, Austria, Brown University, USA, Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bengaluru and the Vienna Zoo conducted a comprehensive study of the Asian Common Toad (Duttaphrynus melanostictus) and its remarkable ability to change colour.

Did You Know? Many frogs and toads, including the Asian Common Toad, participate in "explosive breeding events" where hundreds of individuals gather to mate for just a few days, often triggered by the first heavy rains of the season. It's a fast and furious race to find a partner. |

The team studied the toads in their natural habitat in Karnataka during the monsoon season in June 2023, observing the explosive breeding events firsthand. To understand how toads perceive colour, they used a colour vision model. This model, based on the known spectral sensitivities of common toads, allowed them to calculate just-noticeable differences (JNDs), which measure how different two colours need to be for a toad to tell them apart. They measured the colouration of live mated males, non-mated males, and females, then used the model to compare these colours under natural daylight conditions. Their results showed that while mated and non-mated males looked very similar to each other from a toad's perspective (low JNDs), both yellow males were strikingly different from brown females (high JNDs), indicating clear detectability.

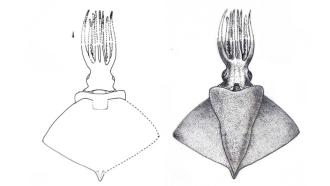

Next, to understand what effect the colour change had on the surrounding toads, the researchers created seven realistic 3D toad models. The model was cast using a preserved Asian Common Toad specimen and filled with polyurethane resin. The models were then painted with non-toxic acrylics to perfectly mimic the spectral reflectance of either a bright yellow breeding male or a brown female. The models were then presented to groups of live male toads in the breeding aggregation. The models were placed about 70 cm apart on a T-shaped stick.

The interactions of the live male toads with these models were video recorded and later analysed by counting instances of physical contact and amplexus (mating) attempts. The setup enabled the researchers to assess how males reacted to different-coloured members of the same species objectively. Finally, to investigate whether male quality played a role, they measured various morphological traits, such as snout-vent length, forearm width, and nuptial pad size.

The study demonstrated that the dramatic transformation during explosive breeding events is indeed a communication strategy. It was used to avoid individuals of the same gender during mate selection, rather than to attract the opposite gender. The team found that this dynamic yellow colouration is easily distinguishable from the brown colour of females from a toad's perspective. Experiments using the 3D toad models showed that live male toads were twice as likely to make physical contact with the brown, female-like models and attempted to amplex (the mating embrace of frogs and toads) them 40 times more often than the yellow, male-like models. This strongly suggests that the yellow colour serves as a clear "stay away, I'm a male" signal to other males, optimising mate-selection and avoiding potentially harmful same-sex interactions in the dense breeding aggregations.

Interestingly, the study also revealed that there were no significant differences in body colour, physical features, or overall body condition between males who successfully mated and those who didn't. This finding challenges the notion that females actively choose mates based on these traits in such a high-pressure, competitive environment, instead highlighting the primary role of the yellow signal in facilitating rapid mate recognition and avoiding costly mistakes.

The research significantly advances our understanding of dynamic sexual dichromatism, a temporary colour change in one sex during breeding. Previous studies on species such as the Moor Frog (Rana arvalis), in which males turn blue, and the Neotropical Yellow Toad (Incilius luetkenii), which also exhibits bright yellow males, have suggested the importance of such signals. This study on the Asian Common Toad reinforces the idea that this rapid, reversible colour change has evolved independently in different anuran species as a convergent solution to the challenges of explosive breeding. It highlights how visual signals can be crucial for quick mate recognition and reducing costly male-male harassment in these time-limited, competitive environments. The study also builds on earlier work suggesting that stress hormones (catecholamines) might mediate the production of these bright yellow colourations, indicating a fascinating physiological link to the breeding frenzy.

However, the study also points to areas for future exploration. While it strongly supports the role of male colouration in male-male interactions, it acknowledges that direct evidence for female mate choice based on these colour traits is still limited, especially given the highly competitive nature of these breeding events, where females have few options. The precise physiological mechanisms that trigger and control these dramatic colour changes also remain largely unknown for most species. Understanding these underlying biological pathways could provide deeper insights into the evolution of such striking adaptations.

Nevertheless, the study provides valuable insights into evolutionary biology and the diverse strategies life employs for survival and reproduction. It has finally provided much-needed answers to the fascinating phenomenon of colour changing and explosive breeding. Moreover, the study reveals the hidden complexities of nature, reminding us that even a common toad has a vibrant story to tell about adaptation and communication.

This article was written with the help of generative AI and edited by an editor at Research Matters.