India has long been known as the land of snakes and snake charmers. Although a misconception, snakes have had a complicated relationship with humans here, from being worshipped by some cultures to being hunted. Amid this complicated relationship, conflicts and snakebites are commonplace, with approximately two million snakebites estimated to occur annually. Recognising the immense scale of this problem, the Indian government has initiated significant efforts. India stands out as the first country to launch a nationwide program specifically targeting snakebite envenomation – the National Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Snakebite Envenoming (NAPSE). Launched in March 2024, this ambitious plan aims to cut snakebite deaths in half by 2030, adopting a One Health approach, which means recognising that human health is deeply connected to the health of animals and our shared environment.

To further strengthen surveillance, snakebite envenomation was made a notifiable disease in November 2024, meaning healthcare providers are now required to report cases to public health authorities. Even India's highest court, the Supreme Court, has taken notice, urging the government and states to improve access to life-saving antivenom and treatments. These steps mark a crucial shift, bringing much-needed attention and momentum to a long-neglected issue.

However, two recent expert commentaries highlight that while these national initiatives are commendable, the path to truly overcoming snakebite is complex and requires careful navigation.

Akhilesh Kumar from Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, and Maya Gopalakrishnan from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, in their formal comment, point out that a national program focused solely on one disease, often referred to as a vertical program, can lead to fragmented services and difficulties in allocating resources where they're most needed. They argue that snakebite isn't a problem that can be fixed with quick solutions like vaccines; instead, it demands fundamental reforms in the healthcare system, shifting from reacting to emergencies to actively preventing them at the primary healthcare level.

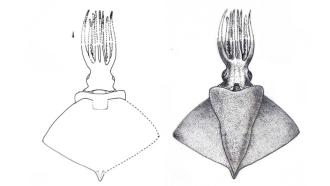

Did You Know? Around 90% of snakebites are caused by the 'big four' among the crawlers - common krait, Indian cobra, Russell's viper and saw-scaled viper. Effective interventions, including education and antivenom provision, would reduce snakebite deaths in India. |

Given India's vast size and incredible diversity, home to over 60 species of venomous snakes, the impact of snakebites varies significantly by region. The current antivenom, effective mainly against the Big Four (common krait, Indian cobra, Russell's viper and saw-scaled viper), often struggles against the unique venom variations found in different parts of the country. And there's no antivenom available for many other dangerous regional species.

This underscores the need for a more localised, collaborative approach. They also caution that relying on a single Centre of Excellence for research might inadvertently limit broader access to research support and funding, suggesting that supporting the entire community of snakebite researchers is vital.

Echoing some of these points, Jaideep C. Menon and Aravind M. S, from the Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, in their commentary, emphasise that health is primarily a state responsibility in India's federal system, meaning individual states must take the lead in implementing policies. They advocate for a balanced approach: a bottom-up strategy for community awareness and empowerment, coupled with top-down directives for initiatives such as ensuring antivenom quality, establishing venom research centres, and addressing legal aspects. They agree on the critical need for more research into the geographical differences in snake venom, how well antivenoms neutralise them, and the economic burden snakebites place on families.

They point to the success of Kerala as a shining example of a decentralised approach, where trained community volunteers, local health workers, and even mobile apps have played a significant role in reducing snakebite deaths. They stress that the Collaborative Centre of Excellence should act as a facilitator, connecting various research groups and generating vital evidence, rather than being seen as the sole solution. They also emphasise the importance of various government departments, including health, animal husbandry, and forestry, collaborating to develop a comprehensive plan.

Bringing these insights together, it's clear that India's fight against snakebite requires a multi-faceted strategy. To truly prevent snakebites and save lives, the government must: empower states to develop and implement their own tailored action plans. Recognise the unique challenges of each region and integrate snakebite care into primary healthcare services, making it accessible at the community level. The government must also invest in research to develop antivenoms that are effective against the diverse regional snake venoms across India. Additionally, it should foster strong community engagement and education programs to raise awareness about prevention and first aid, and ensure robust, sustained funding for these initiatives.

Beyond the health sector, a collaborative effort involving departments like animal husbandry, forestry, and agriculture is crucial to address the complex interplay between humans, snakes, and their environment. By adopting a truly decentralised, integrated, and research-driven approach, India can transform its efforts and significantly reduce the devastating impact of snakebite envenomation.

This article was written with the help of generative AI and edited by an editor at Research Matters