Have you ever found yourself agonising over a decision, replaying different scenarios in your head, and feeling that internal tug-of-war and indecisiveness? This common experience of cognitive conflict is something we all face, whether it's deciding what to wear or grappling with more complex moral dilemmas. Researchers are now looking at our eyes to understand this internal struggle better, finding that how we look can reveal a lot about how we think when faced with difficult choices.

Let’s say you're presented with a tricky ethical question, like the classic trolley problem where you have to decide if sacrificing one person can save many. These situations often don't have a clear right answer, and our minds can wrestle with the conflicting values and potential outcomes for a long time. On the other hand, solving a logic puzzle, like a syllogism, usually involves following a set of rules. If you follow the rules correctly, you should arrive at a definitive answer. But what happens when you get stuck, or when the answer you reach doesn't seem to fit with what you expected? Researchers from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kanpur explored these differences by tracking people's eye movements as they tackled these kinds of problems.

Did you know? Our pupils can change according to ambient light conditions? In low-light conditions, the pupil dilates so more light can reach the retina to improve night vision. In bright conditions, the pupil constricts to limit how much light enters the eye. |

The study used a method called the switch paradigm. Participants were asked to make choices, and at any point during their deliberation, they could press a button to indicate their current preference. If they kept pushing the same button, it meant they were sticking with their current choice (a no-switch block). But if they switched to the other button, it signalled a change in their preference (a switch block). The researchers hypothesised that more frequent switching would mean more cognitive conflict.

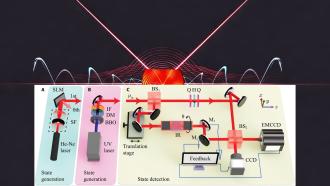

To get a more detailed look at what was happening in their minds, they also used eye-tracking technology. They specifically looked at two things: how long people stared at the screen (fixation duration) and how much their pupils dilated. Longer stares and wider pupils can be signs of increased mental effort and attention, which are often associated with cognitive conflict.

The study showed that when people were dealing with moral dilemmas, which often lack clear-cut answers, their eyes showed signs of sustained conflict. This meant their gaze lingered longer, and their pupils were more dilated, even when they weren't actively switching their stated preference. This suggests that even if someone seems to be leaning towards one option, the internal debate is still going on.

In contrast, when people solved logic problems, the signs of conflict, like longer fixations and dilated pupils, were more pronounced, specifically during the switch blocks, when they were changing their minds. This indicates that in problems with clear rules, conflict tends to pop up when the rules lead to an unexpected or contradictory outcome, prompting a re-evaluation.

Earlier studies often relied on overall reaction times or self-reported feelings of conflict, which don't capture the dynamic, moment-to-moment experience. By using eye-tracking alongside the switch paradigm, the researchers of the new study could pinpoint when and how conflict unfolds during the decision-making process. One limitation with this approach according to the researchers is that in the moral dilemma experiment, they couldn't define specific areas of interest on the screen because the deliberation period was long, and participants might have been looking all over the problem. Future research could refine this by defining specific areas to focus on. Also, using the same participants for both types of tasks in future studies could offer even more precise comparisons.

The insights from this research have practical implications for understanding how we make decisions, especially in areas like education, therapy, and even artificial intelligence. By understanding the subtle cues of cognitive conflict, we can develop better tools and strategies to help people navigate complex choices. In the broader societal context, this research helps us appreciate the complexity of human decision-making, particularly when faced with ethical quandaries that don't have easy answers. It highlights that our internal thought processes are often more fluid and dynamic than we might realise, and our eyes can be a window into this intricate mental landscape.

This article was written with the help of generative AI and edited by an editor at Research Matters.