Water pollution is a critical crisis affecting communities worldwide. The challenge is so significant that the United Nations has made clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) a key global goal. But how do we get young people, the future stewards of our planet, to truly grasp the complexities of this issue and feel empowered to act? A new study delves into this question, revealing how an innovative educational program, centred on tiny organisms called diatoms, is transforming students' understanding and attitudes toward river environments across India, Japan, and the United States.

Researchers from Tokyo Gakugei University, Japan, Tokyo Diatomology Lab, Japan, The Open University of Japan, Agharkar Research Institute, Pune, St. Cloud State University, U.S.A, The University of Tokyo, Japan, and The National Museum of Nature and Science, Japan, implemented a unique educational program in secondary schools across these three diverse nations. They found that students’ environmental awareness significantly increased after participating in the lessons.

Living diatoms comprise a significant portion of Earth's biomass, accounting for approximately 25% of the oxygen produced on the planet. They are also used to monitor past and present environmental conditions, and are commonly used in studies of water quality. |

Before the program, many students, particularly in India, focused on immediate, everyday concerns, like disease and polluted water, often mentioning visible garbage. Japanese students tended to use more abstract terms related to their living environment. American students, living in generally cleaner areas, usually described rivers in terms of natural beauty and wildlife.

However, after the program, a shift had occurred. Students began to think more broadly, incorporating ideas of international and historical comparisons, and considering how river conditions could be improved over time. Indian students, for instance, started discussing global comparisons and the need for sewage treatment plants, showing a deeper understanding of the causes and solutions to pollution. Japanese students shifted towards concepts of social improvement and technological solutions. At the same time, their American counterparts expanded their perspective to include global awareness and concrete actions, such as building sewage treatment plants.

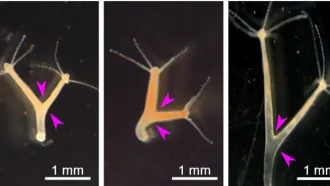

The researchers achieved this shift in thinking with a diatom-based educational program. Diatoms are a large group of microscopic, single-celled algae that live in water and soil, occurring in a variety of shapes and forms, such as ribbons, fans, zigzags, or stars. Diatoms are also excellent bioindicators, meaning their health and diversity are closely related to the level of water pollution. Moreover, their glassy outer shells don’t decay, meaning scientists can examine diatom specimens from centuries ago and compare them to modern samples from the same river.

This program used this unique characteristic to improve learning. Students were shown actual diatom specimens collected from rivers in India, Japan, and the U.S., both from the past (sometimes decades or even a century ago) and from the present day. They also saw photographs and videos of these rivers from both periods. To make the learning even more interactive, the program incorporated SimRiver, a computer simulator. This simulator enabled students to virtually manipulate environmental factors and observe how different water conditions impacted diatom communities, effectively allowing them to travel back in time and understand how human activities had altered rivers.

After engaging with these materials, students were asked to describe their thoughts on river environments, and their responses were then analysed. This allowed the researchers to track changes in vocabulary and conceptual understanding, revealing the shifts in awareness.

The results also showed significant cultural differences in attitudes. A relatively high proportion of Indian students expressed autonomous and action-oriented attitudes, reflecting an internal motivation likely shaped by their learning and daily exposure to polluted rivers. Japanese students frequently showed concern for environmental issues but often reflected "other-dependent thinking" (e.g., "people should do X" or "I expect X to happen"). U.S. students offered fewer behaviour-related responses overall, which might be attributed to their relatively well-preserved local environment, the geographical disconnect of lesson materials, and shorter written responses. However, those who did express opinions often demonstrated autonomous thinking.

This research highlights the need for technological solutions, like computer simulations, and participatory actions in environmental education. While simulators like SimRiver are excellent for helping students understand complex cause-and-effect relationships over long periods, they lack a tangible connection to the real world. By integrating actual diatom specimens and historical river photographs, this program provided that crucial real-world link, making the abstract concepts of water quality and environmental change much more concrete and relatable.

However, the study also highlighted some limitations. For instance, while the changes in awareness were relatively consistent across the Indian student groups, the generalizability of the findings for Japanese and U.S. students remains uncertain and warrants further comparative studies. Additionally, the researchers noted that U.S. students often provided shorter responses, which might be due to their relatively cleaner local environments or a geographical disconnect from the more polluted river examples shown in the lessons.

Ultimately, this work offers a powerful blueprint for environmental education. By helping students understand the historical journey of their local rivers and comparing it to global contexts, the program fosters a deeper awareness of water pollution. More importantly, it helps students develop action-oriented attitudes, where they not only understand the problem but also start thinking about solutions and what they can do. This is a crucial step towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6, empowering the next generation to become active participants in solving global water challenges.

This article was written with the help of generative AI and edited by an editor at Research Matters.