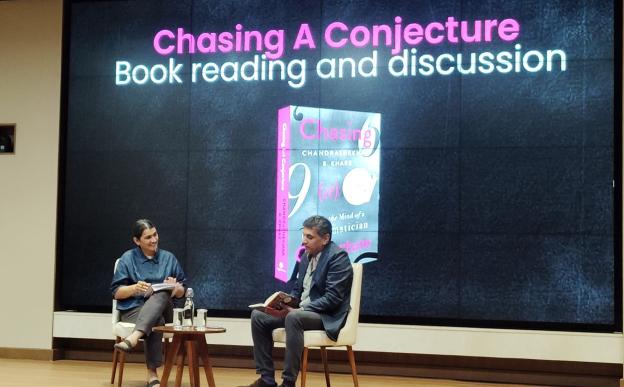

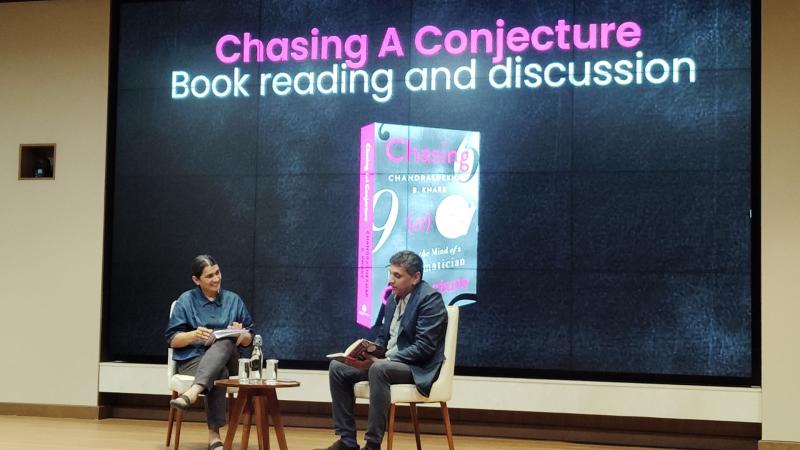

In the world of high-stakes mathematics, few challenges equal the pursuit of a major conjecture, which is an unproven guess that promises to unify vast areas of the discipline. For Professor Chandrashekhar Khare, FRS, a mathematician and winner of the Infosys Prize (2010), this pursuit became the subject of his recent book, Chasing the Conjecture. In a candid interaction with Research Matters, Prof. Khare discussed not only the decades-long quest that led to his landmark proof but also the personal, philosophical, and cultural motivations that drive a life dedicated to pure science.

Khare’s journey began far from the hallowed halls of Cambridge or the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), where he did much of his work. He started instead in Mumbai. He recalls a youth drawn to three main intellectual interests: "math, music, and literature." The decisive moment came when a professional mathematician, a "charismatic individual", visited his home and revealed the depths of even the simplest concepts, like the 5th-grade division algorithm. This interaction posed intriguing questions, including one related to what he later learned was the Chinese Remainder Theorem.

"It seemed like a world which is a mystery, a world which one would want to know more about," Khare recounts.

This early spark led him inevitably to number theory, a field he reveres. Number theory, he explains, has an irresistible charm because it deals with "the simplest of all mathematical objects... 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and so on. It allows one to ask very simple-minded questions, which a high schooler can understand, but the solutions turn out to be very, very elaborate often" he remarks. This delicate balance of simplicity in question and complexity in resolution, combined with its exalted status as the 19th-century mathematician Gauss declared, "number theory is the queen of mathematics", cemented Khare's dedication.

The Long Road to Proof

After formative years at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), which provided the essential time and isolation needed for his mathematical development, Khare embarked on the central project of his career: chasing a key conjecture in the field.

In mathematical terminology, a conjecture is simply

"a guess which a mathematician makes. It is something which you think should be true and which you cannot prove at the moment." To move from a conjecture to a proven theorem requires a monumental effort, because, as Khare states, "in mathematics, proof is the holy grail. You have to prove everything."

The specific question that captivated him was Serre’s conjecture, a statement by the 20th-century mathematician Jean-Pierre Serre. Khare was drawn to it because it was "a very broad question," central to his subject, and highly challenging. The process was a decade-long struggle, from 1995 to the breakthrough in 2004, followed by several years of collaborative work with Jean-Pierre Wintenberger in Strasbourg to complete the proof.

At its core, Serre’s conjecture is about identifying a hidden unity. Khare describes it as bringing together two seemingly disparate structures, which he labels “Galois symmetries” and “Ramanujan symmetries.” His work demonstrated that these two types of symmetries, which, according to Khare

“appear totally different, actually have the same DNA. They are one and the same.”

This structural unification is precisely what makes the result so significant, as it not only implies a fresh proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem but also contributes a crucial fragment to the even vaster Langlands Program, a comprehensive vision for number theory formulated in the 1960s.

Mathematics as Cultural Heritage

For Khare, the book Chasing the Conjecture is much more than a narrative of this specific mathematical feat. It is also a cultural artefact and a literary memoir.

“Writing it was a struggle; it took almost 4-5 years, including a year of editing, to find the right structure that could convey three things: the mathematics, the mathematician, and the process of doing mathematics”, notes Prof Khare.

The main motivation was philosophical: to show the general public that mathematics is an essential part of the cultural heritage of humankind, standing alongside painting, music, and literature. While people recognise its usefulness, that "Planes wouldn't fly, computers wouldn't be possible without the underlying mathematics", they often fail to appreciate it as an intellectual discipline.

Khare acknowledges that the subject has an "unearned reputation of being forbidding esoteric," often compounded by poor school experiences. He sought to write in a language that would "plunge the reader into the world of mathematical research," presenting the atmosphere, vulnerability, and sheer dedication required for the creative pursuit.

He hopes the book will convey "the experience of being a mathematician, the experience of doing mathematical research and the richness of the subject."

Investing in India's Future

Turning to the future, Khare, an Infosys Prize winner and who has served on the Infosys Science Foundation jury, is optimistic about the potential for mathematics in India but stresses the need for greater investment and a shift in perception.

He notes India’s "very rich long history of mathematics," citing figures like Madhava and Ramanujan, and highlights the high-quality post-independence work. India, he argues, is now in a position to push ahead, but this requires nurturing the talent pool.

"I feel that the future can be very bright and should be very bright because we do have a lot of talent," Khare asserts.

He draws a vivid analogy to cricket, noting that massive investment and resources mobilised talent through initiatives like the IPL, leading to cricketers emerging from across the country. A similar focus is needed in pure sciences.

Crucially, he addresses the common school-level perception that mathematics is a "done subject" or too tough, explaining that the "unknown is always much more than what is known." While he agrees that "mathematics is tough, so there is no sugar coating," he believes students and the country at large respond to the challenge. He concludes that basic science, particularly mathematics, is the ultimate long-term investment:

"In a sense, you need basic science to make technological advances possible... training the people here... brings the greatest strength to the country and there are long-term dividends."

To understand the journey and get inside the mind of a mathematician, grab a copy of the book.